In this guide, we’ll cover the rule of cropping images with humanoid subjects, or rather, the concept of “limb chopping.” We’ll start with a quick overview of the rule and how to apply it, then go into more detail so you can understand it—and learn how to break it. The rule, mind you, not the limbs.

The what?

As the name implies, a limb chop happens when you crop an image in a way that cuts off part of a limb. You’re not required to show every limb in every shot, but there are better and worse places to cut them off.

The where?

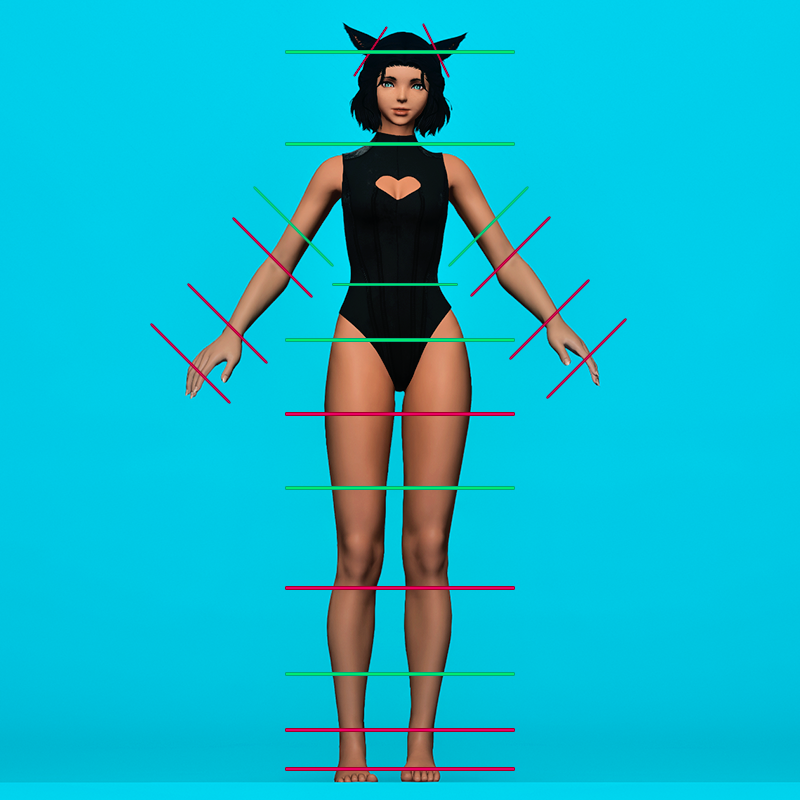

The image above shows a chart illustrating where you can—and can’t—chop your subject. It’s a useful reference, but I don’t expect you to save a picture of my character just to check it every time you crop an image. Instead of memorizing the chart, it’s easier to remember a few simple rules:

- When you crop, do so in a way that it looks intentional.

- Don’t crop at joints or otherwise bendy areas.

- Crop above the hairline, or far enough below it that it doesn’t look like your character is balding.

- Don’t crop through fingers or toes. (This one can be a bit controversial. My advice is to avoid it when you can, but don’t live by this rule.)

The why?

When part of a body suddenly goes missing, it can be a bit jarring. Even if it only registers subconsciously, it can create a sense of discomfort. More importantly, a poorly cut limb can create the illusion that it extends much farther than it naturally should.

I always feel this particular image of the footballers illustrates this point perfectly. By cutting off the arm at the wrist—and having someone else raise their arm at a similar height—it makes the center man’s arm look far longer than it should be.

Avoiding bad chops

Avoiding bad chops starts with taking your shot in a way that gives you options later. While you can adjust colors and lighting fairly easily in post-processing, you can’t magically grow a missing limb back onto your character. If you didn’t capture it, you can’t bring it back.

So, as you take your screenshots, keep an eye on the limbs and where your subject is being cut off. Shooting a little wider than your intended final crop gives you more freedom during editing. And if you’re working at a high resolution, you don’t need to frame it perfectly in the moment—unless you’re absolutely opposed (for whatever reason) to a little editing afterwards.

Intent & creativity

All rules are meant to be broken, and that goes for this one as well. This doesn’t mean you should start cropping straight through your character’s chin—no matter what, that will always look terrible. It does mean you’re allowed to experiment, bend the rules, and get creative.

I mentioned this earlier in the guide, but it applies here more than anywhere else: whatever you do, make it look intentional. With composition, that matters even more. If something feels deliberate, it doesn’t matter as much whether it follows the rules.

Secondary subjects

The way you crop secondary subjects doesn’t always follow the same rules as cropping your primary subject. Characters that are out of focus, or used to frame the shot, aren’t treated the same way as the main subject of your image.

As you can see above, my character isn’t cropped. In the foreground, however, there are two characters cropped in ways we’d normally avoid.

Thanks to the depth of field effect, the crop doesn’t feel awkward or distracting. Instead, it helps frame the image in a flattering way, drawing your attention to the character in the center.

That said, you still shouldn’t crop secondary subjects blindly. Their placement and framing should serve a purpose.

Emphasis

Normally, I’d advise against cropping straight through your subject’s face. However, a creative and strategic crop can completely change the emotion your image conveys.

In the above example we can see that by cropping through the character’s face, emphasis is placed on the action in the shot. The emotion no longer comes from expression, and more meaning is added to the touch against the gem. It’s an intentional action rather than anything else.

In the examples above, cropping through the character’s face shifts the focus onto the action in the shot. The emotion no longer comes from expression—instead, the meaning moves to the touch against the necklace. It becomes an intentional gesture, rather than just a pose.

In the first image, we can tell the character is resting her hand on her chest, but not necessarily with any clear purpose. She could be referring to herself, or she might simply have it raised mid-conversation.

In the second image, the emphasis lands on the action itself, which adds clarity to the intent behind raising the character’s hand and in turn touching the necklace. Maybe it means something to her. Maybe she’s reminded of something and reaches for it without thinking.

By cropping more creatively, we create a much more interesting narrative—one that wouldn’t exist otherwise.

References

This guide was written using the following references: